And in the beginning was the grain or the heavenly gift of wheat

by prof. Giovanni Mannara

Prof. Giovanni Mannara

The art of cooking is a religious gesture. It is therefore not surprising that the Greek term μάγειρος (màgeiros) indicates, in ancient Greece, both the cook and the butcher who has the task of sacrificing the animal for the ceremony. Sacred rites for the Olympic gods and human banquets, therefore, are the scenario of a community that found itself in food. The fumes of the sacrifices arrived on Olympus, dense and pasty, which, rising from the altars, mingled with the nectar and ambrosia with which the gods nourished themselves while, on earth, the heroes feasted on roasted meats on spit with a sharp point drinking wine. Furthermore, gods and goddesses were immense tutelary gods of food and ritual social occasions. Above all, the equivalent of the Roman Ceres, stood Dèmetra, defined by Homer χρυσαόρου ἀγλαοκάρπου (chriusaòru aglaocgàrpu) or “by the golden sword, Lady of the seasons”: she is the one who watches over the agricultural Mediterranean condensed in the wheat. And so from Crete and Eleusis to Sicily, wheat becomes sacred and to Triptolemus, made immortal by the divinity, is entrusted with the task of teaching the generation of men its cultivation. That grain, pregnant with life, will thus become man’s companion in its path of civilization and progress, marking the transition from nomadism to permanent nature. Totemic, fascinating and iconic entity, for which Frazer could rightly speak of the “spirit of the wheat” as a panic and indelible figure of the Mediterranean (J. Frazer, The Golden Branch, Rome, Newton Compton Editori, 2009, p. 123).

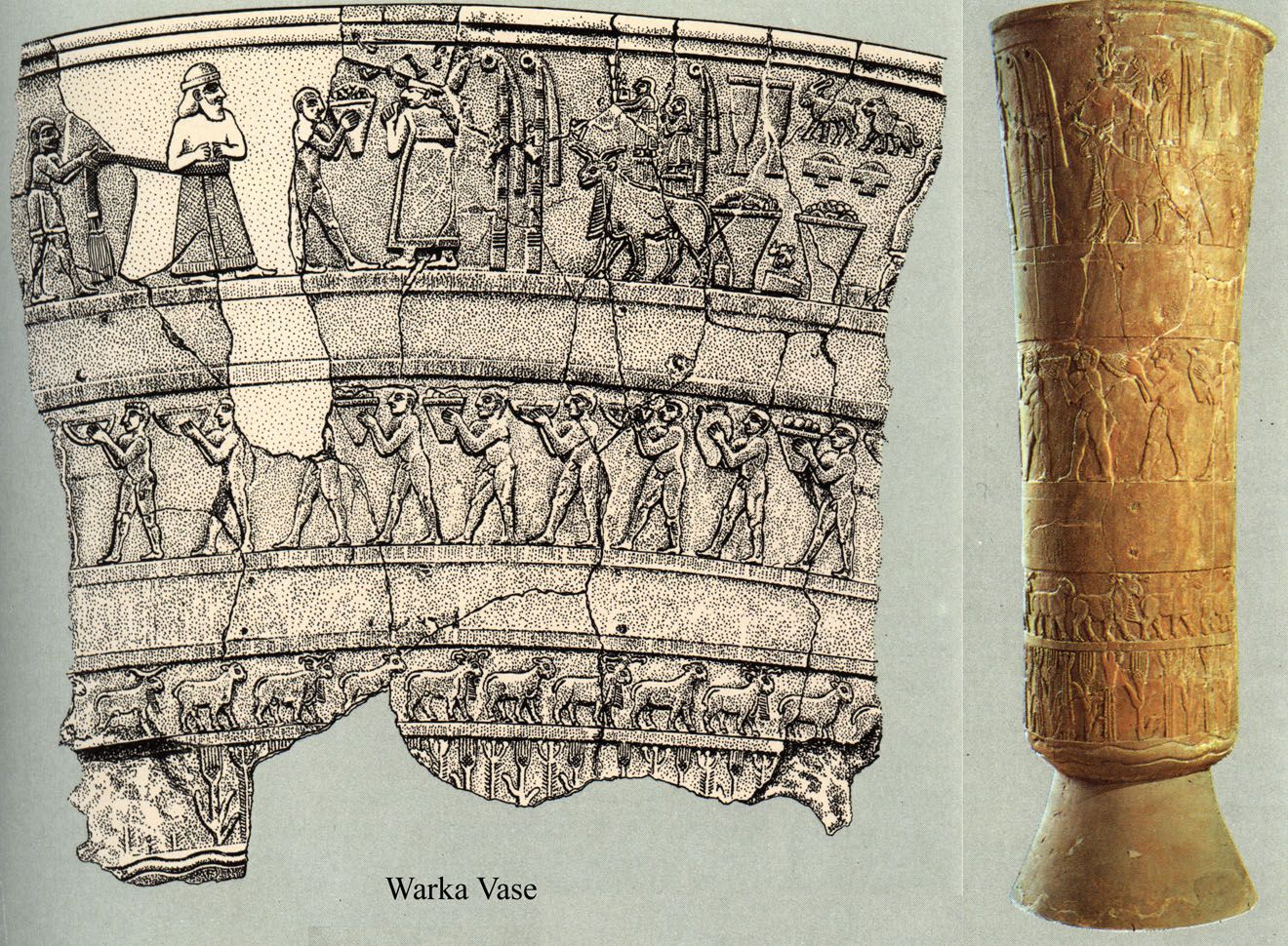

Representative, to this merit, is the vase discovered in the proto-Sumerian city of Uruk (today’s Warka), in Mesopotamia, and datable to the fourth millennium BC. In alabaster, decorated with horizontal bands in relief, it has ripples of water in the lower register from which reeds and sprouts of wheat emerge which become support for the whole creation that develops in a vertical position. A narrative and artistic vision with a cosmic breath that, from the empirical sensible, dates back to the theophanic royal manifestation.

It also reads in the Iliad (XIII, 322) as Homer, to indicate the assembly of civilian men, precisely uses the expression “grain eaters”. To corroborate this hypothesis of civilization, remember the figure of the mythical cyclops Polyphemus who, lives secluded, does not work either wood or metals but above all “did not resemble / a man who eats bread, but resembled the wild peaks / high mountains, which it appears isolated from the others “(Homer, Odyssey, IX, vv. 190-192). To be called men, then, one must feed on that ground of the goddess with blond hair like ripe wheat. Demeter herself, however, would have invented the mill and the plow. The first description of an agricultural scene is found in book XVIII of the Iliad about the sparkling shield of Achilles, forged for him by the god Hephaestus. A refined moment of ekphrasis which, effectively interrupting the narrative, opens a gash on that bucolic world where the black earth becomes golden for its fruits. It reads: «[…] the reapers / reapers; / […] the grain partly on the furrow fell thickly on the ground, / […] of the young, carrying the ears with their arms, / they gave them continuously. The king […] / holding the scepter, stood on the furrow, cheerful in heart “(Homer, Iliad, XVIII, vv 550-560). Among the multiple artistic, clay and statuary testimonies, closer geographically to us and of greater aesthetic appeal, we are here to report the Acroliths of Demeter and her daughter Kore, datable around 530 BC, exhibited at the museum of Aidone in the province of Enna. As seated and immobile, as in the ancient ναός (naòs) of a temple, wrapped in a timeless aura, the goddesses await visitors who thank them, still today, for the heavenly gift of the ear.

From wheat to bread. And then to pasta, the step, or rather the dish, is “short”. In 1154, the Arab geographer Edrisi made mention of a flour food in the form of threads, the “triyah” prepared in Trabia (today’s Palermo). And from there, pasta becomes vital food for the masses. Moreover, it is very significant that even the poet Hesiod, to indicate the ear, uses the word βίος (bìos) which, in a much more immediate way, means “life”.

Prof. Giovanni Mannara

Teacher of Letters, Italianist, Art Historian, he prefers classical and Baroque literature.

Virtuous esthete with an D’Annunzian spirit.

Lord of other times, with his refinement and elegance he makes us appreciate and taste history, culture and art.

Leave A Comment